Redux Fundamentals, Part 2: Concepts and Data Flow

Redux Fundamentals, Part 2: Concepts and Data Flow

- Key terms and concepts for using Redux

- How data flows through a Redux app

Introduction

In Part 1: Redux Overview, we talked about what Redux is, why you might want to use it, and listed the other Redux libraries that are typically used with the Redux core. We also saw a small example of what a working Redux app looks like and the pieces that make up the app. Finally, we briefly mentioned some of the terms and concepts used with Redux.

In this section, we'll look at those terms and concepts in more detail, and talk more about how data flows through a Redux application.

Note that this tutorial intentionally shows older-style Redux logic patterns that require more code than the "modern Redux" patterns with Redux Toolkit we teach as the right approach for building apps with Redux today, in order to explain the principles and concepts behind Redux. It's not meant to be a production-ready project.

See these pages to learn how to use "modern Redux" with Redux Toolkit:

- The full "Redux Essentials" tutorial, which teaches "how to use Redux, the right way" with Redux Toolkit for real-world apps. We recommend that all Redux learners should read the "Essentials" tutorial!

- Redux Fundamentals, Part 8: Modern Redux with Redux Toolkit, which shows how to convert the low-level examples from earlier sections into modern Redux Toolkit equivalents

Background Concepts

Before we dive into some actual code, let's talk about some of the terms and concepts you'll need to know to use Redux.

State Management

Let's start by looking at a small React counter component. It tracks a number in component state, and increments the number when a button is clicked:

function Counter() {

// State: a counter value

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0)

// Action: code that causes an update to the state when something happens

const increment = () => {

setCounter(prevCounter => prevCounter + 1)

}

// View: the UI definition

return (

<div>

Value: {counter} <button onClick={increment}>Increment</button>

</div>

)

}

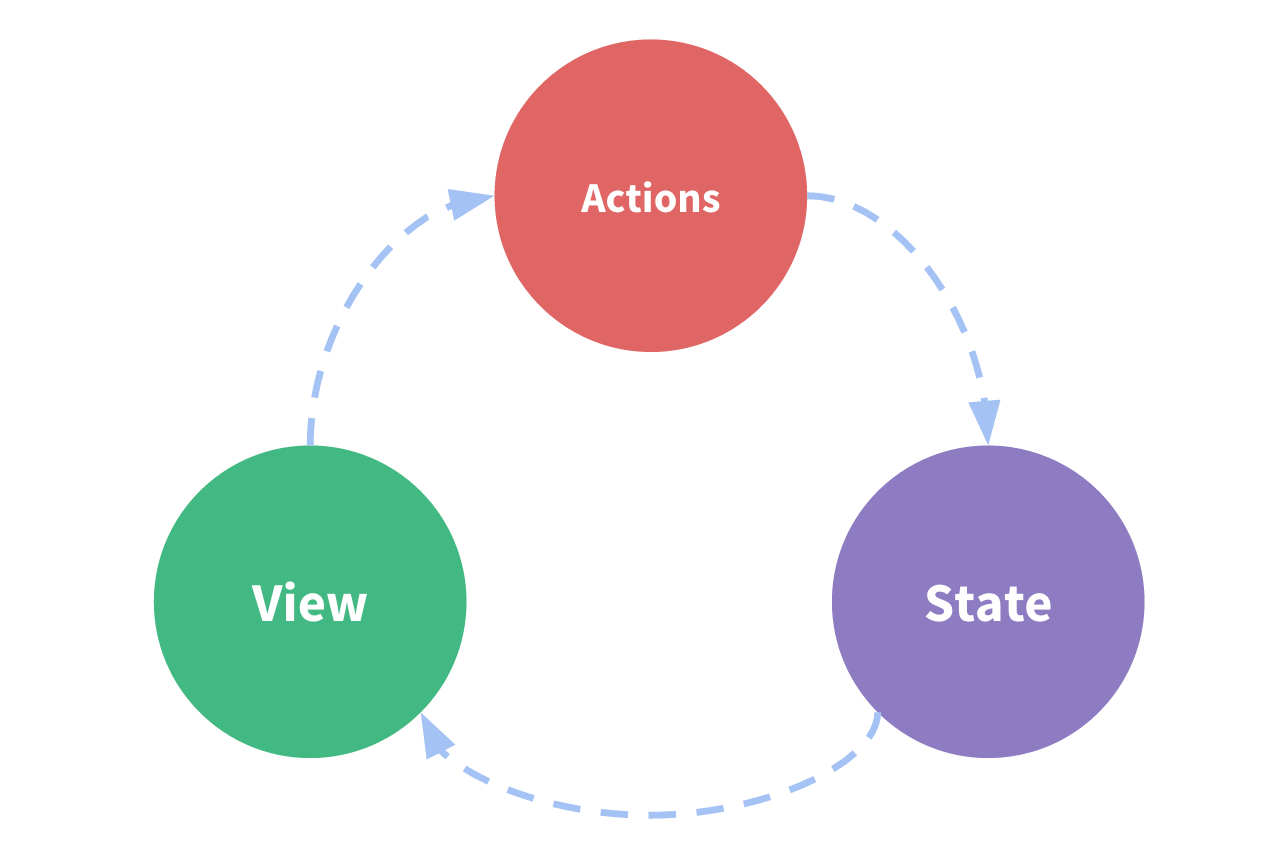

It is a self-contained app with the following parts:

- The state, the source of truth that drives our app;

- The view, a declarative description of the UI based on the current state

- The actions, the events that occur in the app based on user input, and trigger updates in the state

This is a small example of "one-way data flow":

- State describes the condition of the app at a specific point in time

- The UI is rendered based on that state

- When something happens (such as a user clicking a button), the state is updated based on what occurred

- The UI re-renders based on the new state

However, the simplicity can break down when we have multiple components that need to share and use the same state, especially if those components are located in different parts of the application. Sometimes this can be solved by "lifting state up" to parent components, but that doesn't always help.

One way to solve this is to extract the shared state from the components, and put it into a centralized location outside the component tree. With this, our component tree becomes a big "view", and any component can access the state or trigger actions, no matter where they are in the tree!

By defining and separating the concepts involved in state management and enforcing rules that maintain independence between views and states, we give our code more structure and maintainability.

This is the basic idea behind Redux: a single centralized place to contain the global state in your application, and specific patterns to follow when updating that state to make the code predictable.

Immutability

"Mutable" means "changeable". If something is "immutable", it can never be changed.

JavaScript objects and arrays are all mutable by default. If I create an object, I can change the contents of its fields. If I create an array, I can change the contents as well:

const obj = { a: 1, b: 2 }

// still the same object outside, but the contents have changed

obj.b = 3

const arr = ['a', 'b']

// In the same way, we can change the contents of this array

arr.push('c')

arr[1] = 'd'

This is called mutating the object or array. It's the same object or array reference in memory, but now the contents inside the object have changed.

In order to update values immutably, your code must make copies of existing objects/arrays, and then modify the copies.

We can do this by hand using JavaScript's array / object spread operators, as well as array methods that return new copies of the array instead of mutating the original array:

const obj = {

a: {

// To safely update obj.a.c, we have to copy each piece

c: 3

},

b: 2

}

const obj2 = {

// copy obj

...obj,

// overwrite a

a: {

// copy obj.a

...obj.a,

// overwrite c

c: 42

}

}

const arr = ['a', 'b']

// Create a new copy of arr, with "c" appended to the end

const arr2 = arr.concat('c')

// or, we can make a copy of the original array:

const arr3 = arr.slice()

// and mutate the copy:

arr3.push('c')

Redux expects that all state updates are done immutably. We'll look at where and how this is important a bit later, as well as some easier ways to write immutable update logic.

For more info on how immutability works in JavaScript, see:

Redux Terminology

There's some important Redux terms that you'll need to be familiar with before we continue:

Actions

An action is a plain JavaScript object that has a type field. You can think of an action as an event that describes something that happened in the application.

The type field should be a string that gives this action a descriptive name, like "todos/todoAdded". We usually write that type string like "domain/eventName", where the first part is the feature or category that this action belongs to, and the second part is the specific thing that happened.

An action object can have other fields with additional information about what happened. By convention, we put that information in a field called payload.

A typical action object might look like this:

const addTodoAction = {

type: 'todos/todoAdded',

payload: 'Buy milk'

}

Reducers

A reducer is a function that receives the current state and an action object, decides how to update the state if necessary, and returns the new state: (state, action) => newState. You can think of a reducer as an event listener which handles events based on the received action (event) type.

"Reducer" functions get their name because they're similar to the kind of callback function you pass to the Array.reduce() method.

Reducers must always follow some specific rules:

- They should only calculate the new state value based on the

stateandactionarguments - They are not allowed to modify the existing

state. Instead, they must make immutable updates, by copying the existingstateand making changes to the copied values. - They must not do any asynchronous logic, calculate random values, or cause other "side effects"

We'll talk more about the rules of reducers later, including why they're important and how to follow them correctly.

The logic inside reducer functions typically follows the same series of steps:

- Check to see if the reducer cares about this action

- If so, make a copy of the state, update the copy with new values, and return it

- Otherwise, return the existing state unchanged

Here's a small example of a reducer, showing the steps that each reducer should follow:

const initialState = { value: 0 }

function counterReducer(state = initialState, action) {

// Check to see if the reducer cares about this action

if (action.type === 'counter/incremented') {

// If so, make a copy of `state`

return {

...state,

// and update the copy with the new value

value: state.value + 1

}

}

// otherwise return the existing state unchanged

return state

}

Reducers can use any kind of logic inside to decide what the new state should be: if/else, switch, loops, and so on.

Detailed Explanation: Why Are They Called 'Reducers?'

The Array.reduce() method lets you take an array of values, process each item in the array one at a time, and return a single final result. You can think of it as "reducing the array down to one value".

Array.reduce() takes a callback function as an argument, which will be called one time for each item in the array. It takes two arguments:

previousResult, the value that your callback returned last timecurrentItem, the current item in the array

The first time that the callback runs, there isn't a previousResult available, so we need to also pass in an initial value that will be used as the first previousResult.

If we wanted to add together an array of numbers to find out what the total is, we could write a reduce callback that looks like this:

const numbers = [2, 5, 8]

const addNumbers = (previousResult, currentItem) => {

console.log({ previousResult, currentItem })

return previousResult + currentItem

}

const initialValue = 0

const total = numbers.reduce(addNumbers, initialValue)

// {previousResult: 0, currentItem: 2}

// {previousResult: 2, currentItem: 5}

// {previousResult: 7, currentItem: 8}

console.log(total)

// 15

Notice that this addNumbers "reduce callback" function doesn't need to keep track of anything itself. It takes the previousResult and currentItem arguments, does something with them, and returns a new result value.

A Redux reducer function is exactly the same idea as this "reduce callback" function! It takes a "previous result" (the state), and the "current item" (the action object), decides a new state value based on those arguments, and returns that new state.

If we were to create an array of Redux actions, call reduce(), and pass in a reducer function, we'd get a final result the same way:

const actions = [

{ type: 'counter/incremented' },

{ type: 'counter/incremented' },

{ type: 'counter/incremented' }

]

const initialState = { value: 0 }

const finalResult = actions.reduce(counterReducer, initialState)

console.log(finalResult)

// {value: 3}

We can say that Redux reducers reduce a set of actions (over time) into a single state. The difference is that with Array.reduce() it happens all at once, and with Redux, it happens over the lifetime of your running app.

Store

The current Redux application state lives in an object called the store .

The store is created by passing in a reducer, and has a method called getState that returns the current state value:

import { configureStore } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

const store = configureStore({ reducer: counterReducer })

console.log(store.getState())

// {value: 0}

Dispatch

The Redux store has a method called dispatch. The only way to update the state is to call store.dispatch() and pass in an action object. The store will run its reducer function and save the new state value inside, and we can call getState() to retrieve the updated value:

store.dispatch({ type: 'counter/incremented' })

console.log(store.getState())

// {value: 1}

You can think of dispatching actions as "triggering an event" in the application. Something happened, and we want the store to know about it. Reducers act like event listeners, and when they hear an action they are interested in, they update the state in response.

Selectors

Selectors are functions that know how to extract specific pieces of information from a store state value. As an application grows bigger, this can help avoid repeating logic as different parts of the app need to read the same data:

const selectCounterValue = state => state.value

const currentValue = selectCounterValue(store.getState())

console.log(currentValue)

// 2

Core Concepts and Principles

Overall, we can summarize the intent behind Redux's design in three core concepts:

Single Source of Truth

The global state of your application is stored as an object inside a single store. Any given piece of data should only exist in one location, rather than being duplicated in many places.

This makes it easier to debug and inspect your app's state as things change, as well as centralizing logic that needs to interact with the entire application.

This does not mean that every piece of state in your app must go into the Redux store! You should decide whether a piece of state belongs in Redux or your UI components, based on where it's needed.

State is Read-Only

The only way to change the state is to dispatch an action, an object that describes what happened.

This way, the UI won't accidentally overwrite data, and it's easier to trace why a state update happened. Since actions are plain JS objects, they can be logged, serialized, stored, and later replayed for debugging or testing purposes.

Changes are Made with Pure Reducer Functions

To specify how the state tree is updated based on actions, you write reducer functions. Reducers are pure functions that take the previous state and an action, and return the next state. Like any other functions, you can split reducers into smaller functions to help do the work, or write reusable reducers for common tasks.

Redux Application Data Flow

Earlier, we talked about "one-way data flow", which describes this sequence of steps to update the app:

- State describes the condition of the app at a specific point in time

- The UI is rendered based on that state

- When something happens (such as a user clicking a button), the state is updated based on what occurred

- The UI re-renders based on the new state

For Redux specifically, we can break these steps into more detail:

- Initial setup:

- A Redux store is created using a root reducer function

- The store calls the root reducer once, and saves the return value as its initial

state - When the UI is first rendered, UI components access the current state of the Redux store, and use that data to decide what to render. They also subscribe to any future store updates so they can know if the state has changed.

- Updates:

- Something happens in the app, such as a user clicking a button

- The app code dispatches an action to the Redux store, like

dispatch({type: 'counter/incremented'}) - The store runs the reducer function again with the previous

stateand the currentaction, and saves the return value as the newstate - The store notifies all parts of the UI that are subscribed that the store has been updated

- Each UI component that needs data from the store checks to see if the parts of the state they need have changed.

- Each component that sees its data has changed forces a re-render with the new data, so it can update what's shown on the screen

Here's what that data flow looks like visually:

What You've Learned

- Redux's intent can be summarized in three principles

- Global app state is kept in a single store

- The store state is read-only to the rest of the app

- Reducer functions are used to update the state in response to actions

- Redux uses a "one-way data flow" app structure

- State describes the condition of the app at a point in time, and UI renders based on that state

- When something happens in the app:

- The UI dispatches an action

- The store runs the reducers, and the state is updated based on what occurred

- The store notifies the UI that the state has changed

- The UI re-renders based on the new state

What's Next?

You should now be familiar with the key concepts and terms that describe the different parts of a Redux app.

Now, let's see how those pieces work together as we start building a new Redux application in Part 3: State, Actions, and Reducers.